Story: The author traces the evolution of the personal computer, including several video game consoles along the way, in terms of both technical features and external appearance. Extensive notes are provided on the histories of the companies that made them, along with a brief esay that places the product in question within the context of that history. And, of course, there are lots of pictures.

Story: The author traces the evolution of the personal computer, including several video game consoles along the way, in terms of both technical features and external appearance. Extensive notes are provided on the histories of the companies that made them, along with a brief esay that places the product in question within the context of that history. And, of course, there are lots of pictures.

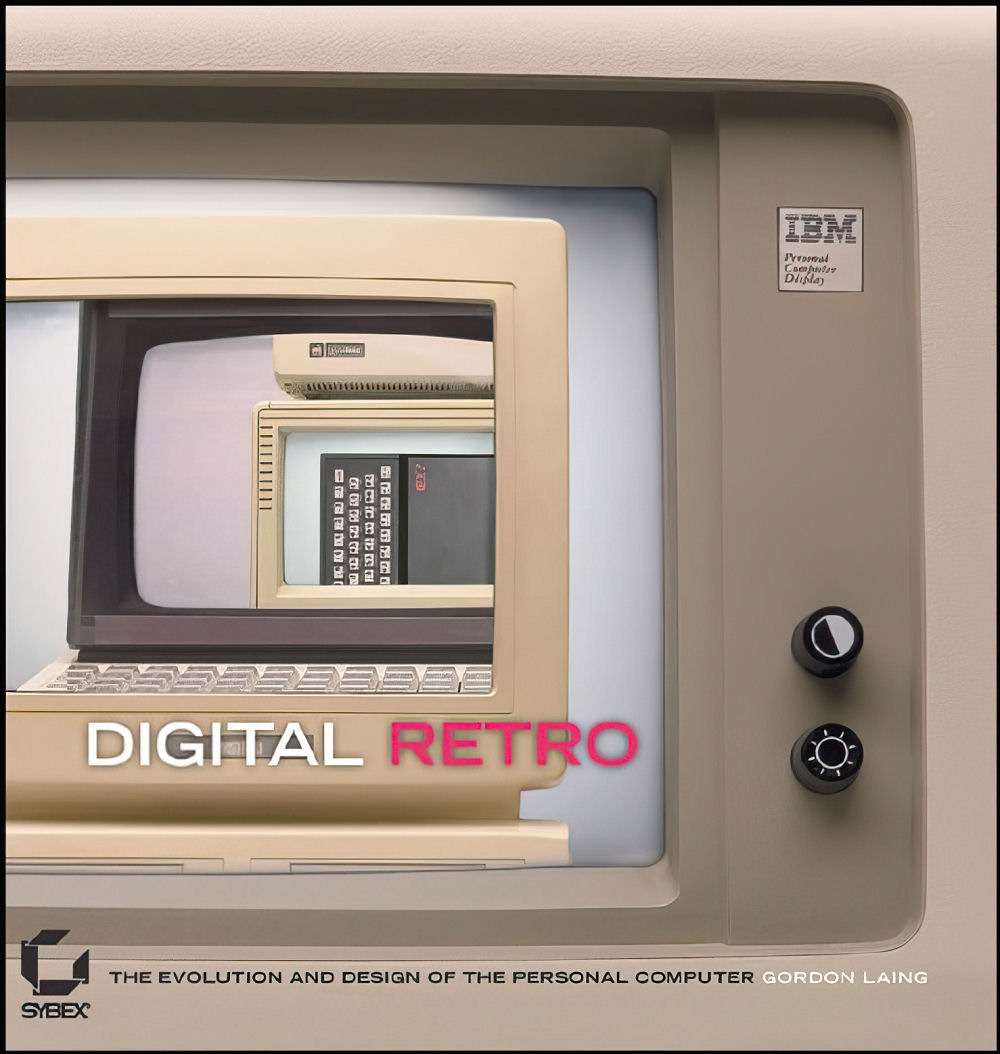

Review: Far more than just a picture book, Digital Retro really takes me back to the early 80s, and the lovingly-photographed full-spread magazine ads for things like the Commodore 64 and the Apple Macintosh. This book takes me right back to those days of “hardware porn,” when young fellows like myself would see computer advertisements and tech specs and would respond with a bit of drool hanging from our chins that would’ve done Pavlov – and Apple’s marketing division – proud.

The pictures are pretty, and they cover nearly every imaginable angle of each machine covered – which is important when a lot of switches, jacks and plugs were tucked away on the back of the machine or on a side panel somewhere. Even the bottom panel of some machines is shown if there’s something interesting about it. But also shown are the tech specs and “killer app” features of each device – even if what was a “killer app” in 1983 isn’t so much of one now.

Gordon Laing’s text is informative, and in itself justifies the purchase price of the book; I learned a great many things here that I hadn’t heard elsewhere. As historical text goes, it’s very even-handed – it seems that, as in the old days when no two computers were compatible with one another and fiercely loyal users’ groups spring up around individual machines like overprotective religious sects, sometimes historians have a hard time telling the story of the personal computer without making a bias or two known. Laing notes when there were rivalries, but he doesn’t get “involved.” So despite this book’s nature making it all too easy to dismiss it as a picture book, its text shouldn’t be discounted.

Another area where Laing is wonderfully even-handed, moreso than with any other book I’ve ever read on this subject, is the international arena. The BBC Micro and the Sony HitBit (an obscure Japanese computer) take their place alongside their much better-known North American counterparts. Laing spared no effort in tracking down seldom-seen hardware to complement his text; within these pages are U.K., European and Japanese computers I’d never seen before, and excellently-preserved specimens of domestic computers that are exceedingly hard to find in good shape (from the MITS Altair 8800 to the NeXT Cube).

I can see where there might be some debate arising about Laing’s inclusion of several video game consoles in Digital Retro, and frankly, I can see both sides of the issue. The Atari 2600, Intellivision, ColecoVision, Vectrex, Sega Master System and Nintendo Entertainment System all get full pictorial coverage here. Are they personal computers? No. Decidedly not. However, they helped to popularize computer equipment with the public. These devices arguably helped to pave the way for a burgeoning personal computer market. So do they belong in “Digital Retro”? I’d say yes – they each get a virtual “guest of honor” badge in a home computer hall of fame.

A tremendously informative book to read – and a fantastic book to just stare at. It reacquainted me with the wonder that was the all-in-one computing behemoth known as the Commodore PET, the very first computer I ever programmed on. It reacquainted me with machines that I used to drool over in magazine ads, only to see them fade into the obscurity of “not enough market share.” “Digital Retro” is an almost-visceral trip down memory lane for old geeks like me, and I highly recommend it.

Year: 2004

Author: Gordon Laing

Publisher: Sybex

Pages: 192 pages