Story: The author traces a history of computer hardware that never happened, ranging from minicomputers that were promised but never mass-produced, to missteps and sidesteps early in the history of personal computing, to unproduced or seldom-circulated also-rans of the early smart phone era. If you love prototype computer hardware, this is an entire book devoted to that topic with a laser-like focus.

Story: The author traces a history of computer hardware that never happened, ranging from minicomputers that were promised but never mass-produced, to missteps and sidesteps early in the history of personal computing, to unproduced or seldom-circulated also-rans of the early smart phone era. If you love prototype computer hardware, this is an entire book devoted to that topic with a laser-like focus.

Review: Fear not – Delete does present the (intended) specs and the stories behind its unrealized hardware. But the introduction to the book lays out the criteria behind much of what was selected, and it’s really there that the reader is told what the book’s real mission is. It’s not to ruminate over capabilities we never got, product lines we should have had, or pieces of gear that could have changed the world. It’s more of a chronicle in retrofuturistic design that nearly made it to market – a travelogue of mid-century-modern design influence in computer hardware.

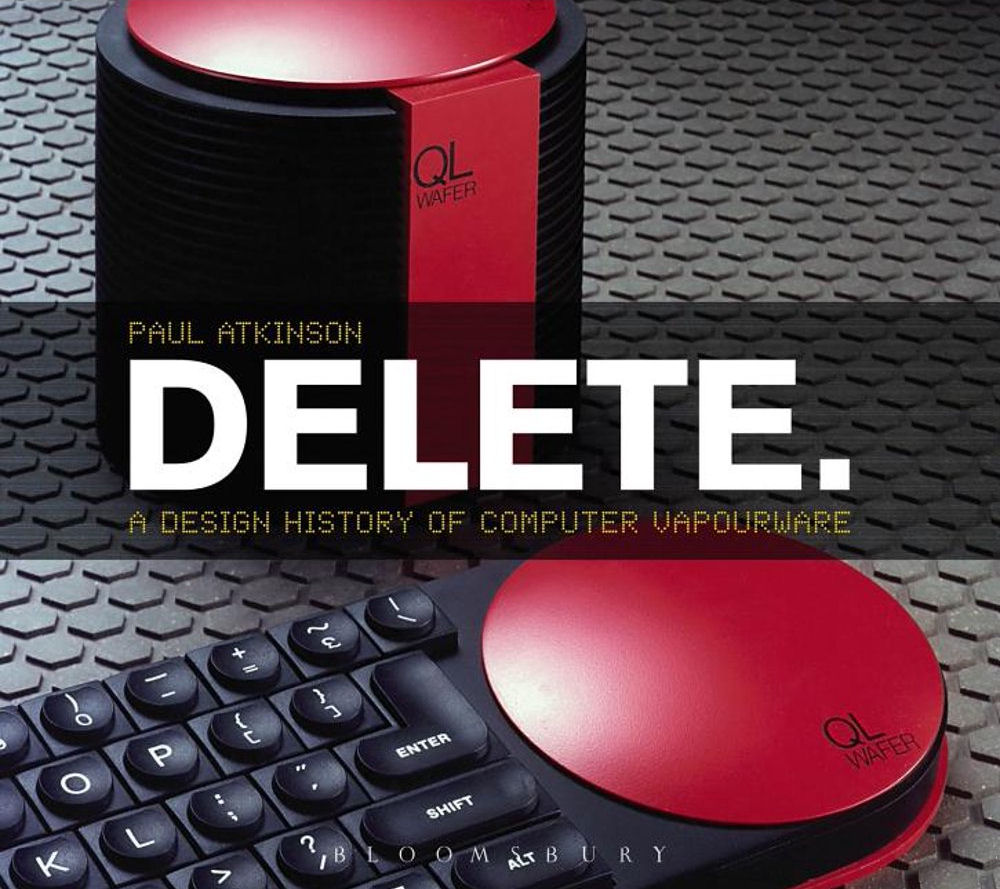

One reader’s retrofuturistic vibe might be another’s vision of the cheesy past, though, so it’s a travelogue full of looks at what the future was going to look like the day after tomorrow… except that internal decision making (sometimes short-sighted) and other market forces dictated that the day after tomorrow in question never happened. IBM internally tried to come up with any number of entry points into the nascent personal computer market, including just licensing the Atari 800 and putting its guts in a more businesslike casing befitting IBM’s brand. Proto-luggables (which could have beaten the Osborne I to its peculiar place in history) and canary-yellow computers that would connect to TV were also in the works and then, for various reasons, suddenly weren’t. The glimpses of other manufacturers’ aborted ideas and best-laid plans are just as tantalizing. Prior to that interval between NExT and the iMac cube, it really seemed to be a primary consideration that computers should look like tools from the future. Some of the form factors are real head-scratchers; others, such as the unproduced wafer-based Sinclair computer prototype on the cover, are things of real beauty.

When the book gets to the point in history where the personal computer revolution was an unstoppable juggernaut, “retrofuturistic” suddenly looks a lot more utilitarian, though maybe we should invent the term retro-utilitarian here – most displays were still cathode ray tubes of various sizes (even for portables)… oh, and by the way, “portable” was a very relative term. Complex, futuristic curved casings were the norm, at least in the prototypes. The necessities of mass-production would likely have reintroduced some rougher edges, but since these unproduced items exist now only in their idealized prototypical state, it calls to mind a song about what a beautiful world it would be.

The book ends on the cusp of the smart phone revolution. As we all know now, the iPhone became the big bang of that particular universe, and yet there were so many near-misses (including some that were nearly made by Apple itself, including a tablet computer that very nearly made it to market in 1991). One of my favorite categories is the variety of smaller-than-laptop portables with keyboards on display. As someone who faithfully lugged an NEC MobilePro around many years past the little machine’s prime, I can tell you that this website is proof positive that such a device was an immensely handy tool for writing on the go. It’s still a bit surprising that it wasn’t a form factor that caught on with the public at large.

Then again, as Delete proves, one reader’s retrofuturistic is another’s “no way on Earth would I carry one of those with me everywhere.” IT all adds up to a fascinating look into some occasionally bizarre, and occasionally wonderful, alternate timelines of the computer industry.

Year: October 24, 2013

Authors: Paul Atkinson

Publisher: Bloomsbury Academic

Pages: 256