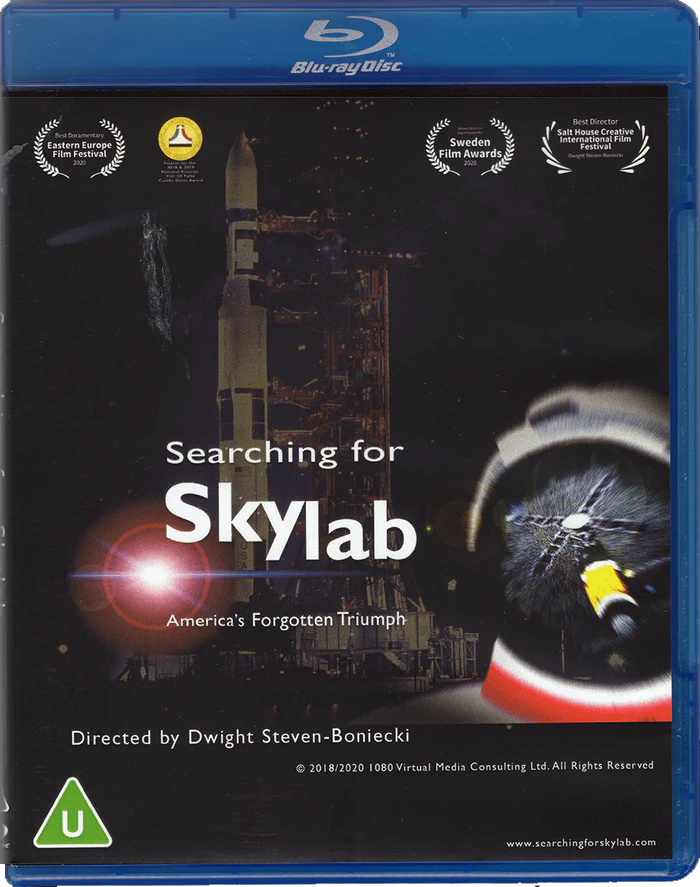

For good or ill, it seems like a lot of documentary films – especially those on niche subjects that aren’t current political-hot-button darlings – have to go the crowdfunding route to even have a chance to come into existence. There’s usually a director/producer/writer at the heart of it who has a vision, and maybe some contacts and inside info on the topic, and not nearly enough money. Their only hope is to find an audience of others who share the same interest. Either a wide audience whose members can pitch in a little bit, or a narrowed audience with deeper pockets, is the project’s only hope. Searching For Skylab is one of those projects, and fortunately it found its supportive audience, because it’s virtually the only documentary on the topic that anyone’s made without the film being bankrolled by the agency that launched Skylab.

And it’s a good thing that it was made when it was, as we’ve since lost interview subjects such as Skylab astronauts Owen Garriott, Gerald Carr, and Paul Weitz, and backup crewmember Bruce McCandless, all of whom are interviewed in depth in Searching For Skylab. Also interviewed are communications engineers from an Australian ground station that was vital to keeping Skylab in constant contact with Houston, family members of other astronauts and engineers who had already passed on, and there’s copious audio from the ground-to-air loops from NASA’s archives. (There have been more books about Skylab than documentary films, and the filmmakers also smartly get interviews with those authors, including the author of this book that was reviewed a while back on theLogBook.media.)

There’s also footage aplenty, ranging from NASA film that can now be seen in high definition, and video from television feeds from the space station, which fares a little less well when viewed in HD, but in many cases, it’s footage that the public hasn’t seen in 50 years, if at all. The story of the unprecedented mission by Skylab’s first crew to salvage the station and make it habitable after the station suffered significant damage at launch is given quite a bit of air time, and rightly so, with equal emphasis on Earthbound engineers’ ingenious solutions to save the station as well as on the astronauts performing spacewalks to implement those solutions. Some of the exchanges between the crew in these tense moments are surprisingly testy – it’s a bit of an eye-opener, but I’m sure nobody wanted to break the already-broken two-billion-dollar space station even worse than it already was.

Significant running time is also given to the topics of life in space, such as eating and “showering”, as well as the student-designed scientific experiments conducted by the crews, a forerunner to the shuttle program’s “getaway specials”. I was pleased to see another shuttle-era forerunner get some attention: the Bruce McCandless-designed mobility unit that later became a practical reality in the shuttle program (and was eventually flown by McCandless himself); the film smartly takes this opportunity to point out that Skylab was part of a continuum that led to the space shuttle program and the International Space Station.

Topics that have almost entered the area of urban legend, such as the possibility that one of the crews might have needed another crew to rescue them, and the so-called “mutiny” of the final Skylab crew, which – as the astronauts involved reveal – was a snafu in a busy communications schedule rather than an instance of astronauts on strike, a notion that the press took and ran with. Also explored in depth is the significant amount of effort that was directed at the newly-detected Comet Kohoutek, whose close pass by the sun merited its own observation campaign from orbit. Possibly the funniest anecdote, however, is a prank Owen Garriott and his wife Helen prepared weeks in advance to confound the ground controllers in Houston, in an attempt to convince them that Helen had driven a home-cooked meal up to the guys aboard the station without anyone at NASA noticing the family station wagon being launched into low Earth orbit.

As a production, I have very minor quibbles with some of the editing, writing, and voice work (all of which are things I’ve done professionally myself), but let’s be honest: most media criticism boils down to “they made different creative choices than I would have made.” It doesn’t mean that any of those elements are necessarily bad, just that, in the filmmakers’ position, I would’ve done some things differently. It’s not a bad movie at all, I just would’ve made different production choices. I grow weary of seeing overdeployed phrases like “weak writing” or “bad directing” or what have you; what the critics really mean to say is “I would’ve done that differently.” And more critics should learn to honestly say that without maximum snark or attitude. And thus ends my harsh criticism of this film – I would’ve done some slightly different things in places stylistically, but no harm has been done to the factual historical information being covered. The details are intact, and we have great interviews with key players in the Skylab story who are no longer with us. Anyone wanting to try their hand at “doing a better Skylab documentary” has run out of time, and interview subjects, to do so. I’m deeply grateful that the filmmakers got these interviews in the can when they did. (Additional interviews are included as bonus features.)

Searching For Skylab is the long-overdue documentary that the Skylab program has always deserved, and it covers most of the major highlights in depth, puts some urban legends to rest, and captures plenty of funny anecdotes that make it an entertaining viewing experience. These stories were captured just in time. Skylab is oft=overlooked because it was perceived by many, quite unjustly, as a letdown after the moon landings. It was a new chapter in the space program that was every bit as important as the moon landings, even if it didn’t generate sexy headlines in the press. And fortunately, its story can now be relived.