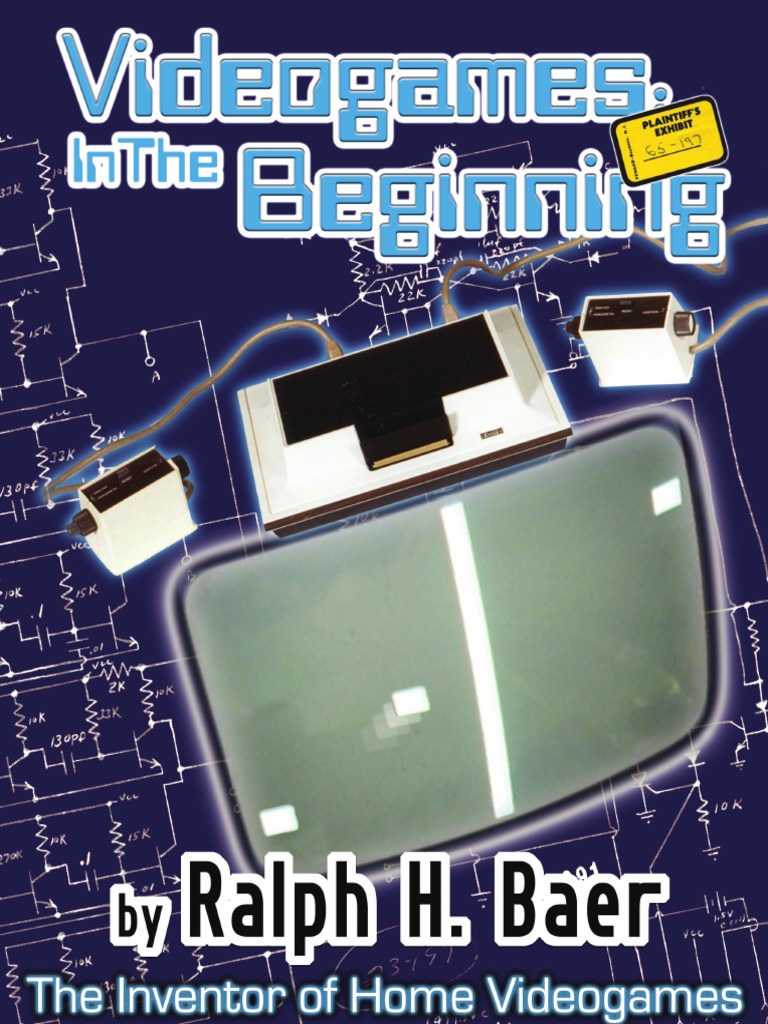

Story: Inventor Ralph Baer, creator of the very first home video game system and the man who holds the patent on interactive games that can connect to an everyday TV (as well as literally dozens of other creations), lays out a detailed chronology of how and when he came up with the idea for “TV games.” Also covered is how he’s dealt with those who have tried to stake their own claims on authorship of the idea, and how he has remained involved with the industry since then.

Story: Inventor Ralph Baer, creator of the very first home video game system and the man who holds the patent on interactive games that can connect to an everyday TV (as well as literally dozens of other creations), lays out a detailed chronology of how and when he came up with the idea for “TV games.” Also covered is how he’s dealt with those who have tried to stake their own claims on authorship of the idea, and how he has remained involved with the industry since then.

Review: In this book, Raph Baer grabs the title of “father of video games,” and spends much of the book backing the claim up with ample evidence. It’s amusing and sometimes a bit enervating to see how many attempts have been made to unseat him from that throne, for a variety of reasons. Atari founder Nolan Bushnell seems to have tried staking his own claim for PR purposes, but that’s not as eyebrow-raising as, say, attempts by Nintendo attorneys in the late 1980s to challenge Baer and his authorship of numerous seminal video game patents so they wouldn’t have to pay hefty licensing fees on the NES. (In the end, Baer says Nintendo settled out of court for a cool $10 million.)

Baer’s habit of fastidiously documenting everything has not only served him well in court depositions, but it’s made this book possible; there’s not only his new retrospective text, but tons of reprinted memos, patent filings, and more. The material covers everything from what he calls the “Eureka document” in which he sketched out his earliest video game ideas on a legal pad, to internal documents from Magnavox and Sanders Associates (the U.S. defense contractor for whom Baer was working when he came up with his earliest gaming ideas), to hand-written notes taken on the floor of early amusement machine operators’ conventions Baer attended to see who was making use of – and money from – his innovations without coughing up the license fees to Sanders or Magnavox. (But things aren’t one-sided – there’s a whole appendix in which Baer admits to borrowing ideas from an Atari arcade flop called Touch Me to create a handheld electronic toy you may have heard of – it’s called Simon.)

Baer seems to have a bit of a vendetta against Atari, but it’s hard to blame him; to this day, Atari’s Nolan Bushnell contends that the Magnavox Odyssey – which predated his Pong arcade game by months – wasn’t a source of inspiration; the evidence (Bushnell’s signature in a guest book for an early Odyssey demo in Burlingame, California, reprinted quite clearly here) and a federal judge’s ruling beg to differ. Not that this has stopped Bushnell from claiming, as recently as the 2003 Classic Gaming Expo (and I was there to hear him say this), that Baer’s Odyssey didn’t inspire Pong, or was “already a commercial failure,” or any number of other escape hatches. Baer may come across as a bit cranky, but nearly 40 years of refuting these claims could do that to a guy. But there’s another side to the book which is positively gleeful – you really pick up on Baer’s excitement whenever he recounts one of his “Eureka” moments. Even when some of the ideas he’s talking about have already become things of the past, he clearly spells out the thinking and the potential behind every concept.

There’s so much history in here that hasn’t been revealed before in other studies of the video game industry, including Baer’s first-hand accounts of some of the earliest cooperative ventures between the military and video game manufacturers for simulation purposes. Refreshingly, this doesn’t become a political issue; if Baer hadn’t done it, someone else would have, so there’s no point in making a fuss about it now – it’s history. And it’s a practice that carries on to this day, whether anyone wants to admit it or not. Other things are just as fascinating, from the endless infringement trials to Sanders’ abortive attempts to dip its toes into the arcade waters. The schematics, even when I don’t understand them entirely, are fascinating too, though sometimes they aren’t reproduced that well; some of them look like very low-resolution faxes or JPEGs. Where the schematics are concerned, however, there’s an offer in the back of the book for a bonus CD-ROM with the full-resolution scans of those documents and several Quicktime videos of Ralph Baer demonstrating the prototype games he and his colleagues created in the late 60s and early 70s. One could conceivably build a cosmetically close – and functionally exact – replica of the Brown Box. The CD-ROM is easily worth the extra ten bucks.

Overall, “Videogames: In The Beginning” is a fun read (and definitely worth the price of admission, with over 200 glossy, full-color overside trade paperback pages), and more informative than even I can adequately describe. The appendix listing the technological innovations first patented by Ralph Baer is mind-boggling: everything from video games to electronic countermeasures to toys to medical gear. That one man could’ve helped to introduce all of these things is amazing – and that he found the time to tell us how it all happened has left us with a book that’s well having on the shelf.

Year: 2005

Author: Ralph H. Baer

Publisher: Rolenta Press

Pages: 258 pages