Story: Replicating a lengthy electronic correspondence, The Odyssey File recounts the collaboration between filmmaker Peter Hyams, who was not only slated to direct 2010: The Year We Make Contact, but to adapt it into screenplay form, and legendary sci-fi author Arthur C. Clarke, who had already published the hotly-anticipated literary sequel 2010: Odyssey Two. The two ruminate over their foray into an untested system for communicating across international distances, discuss the often large changes Hyams wished to make to Clarke’s story, and slowly but surely, get a movie made.

Story: Replicating a lengthy electronic correspondence, The Odyssey File recounts the collaboration between filmmaker Peter Hyams, who was not only slated to direct 2010: The Year We Make Contact, but to adapt it into screenplay form, and legendary sci-fi author Arthur C. Clarke, who had already published the hotly-anticipated literary sequel 2010: Odyssey Two. The two ruminate over their foray into an untested system for communicating across international distances, discuss the often large changes Hyams wished to make to Clarke’s story, and slowly but surely, get a movie made.

Review: As a long-time admirer of both filmed instances of Arthur C. Clarke’s genre-defining saga, I naturally already have a battered, not-getting-any-younger copy of Clarke’s The Lost Worlds Of 2001, a book that’s about as old as I am, and it’s fascinating stuff, mainly offering glimpses into roads not taken by Stanley Kubrick’s original 1968 film. The close collaboration between Kubrick and Clarke is very well documented. And so, it turns out, is the much more space-age collaboration between Clarke and 2010 director/screenwriter Peter Hyams.

I wasn’t yet into my teens when the movie adaptation of 2010 was released, and didn’t read Clarke’s novel that inspired the movie until years later. I know it’s a popular pastime to bash 2010 and point out that it’s in no danger of equaling 2001. But a movie needs to tell a story, and what Odyssey Two was…was really a pleasant travelogue in which Clarke showed off how scientifically accurate and up-to-date science fiction could be in the face of current and ongoing missions revealing more about Jupiter. There are incidents in the book, things do happen, but there’s precious little dramatic tension in Clarke’s telling of the tale. And by the time one is halfway through The Odyssey File, one strongly gets the impression that Clarke knew that all along. Every change Hyams makes to the story makes it more dramatically satisfying, and doesn’t dent Clarke’s vaunted scientific accuracy at all. Sorry, Clarke worshippers, but Hyams’ 2010 is a stronger narrative than Clarke’s 2010.

The softball criticism often lobbed at the movie is that its Cold-War-extrapolated-into-the-21st-century backdrop dates it badly (a criticism of which I myself was guilty at a time when it seemed international tensions had subsided permanently), and yet here we are, two decades into the 21st century, and the Cold War turns out to have been as enduring as new wave music and the Atari 2600. All the classics are back, whether we want them back or not, so hopefully you still have your Hammer Pants on hot standby. Perhaps the biggest surprise of this book is that Clarke offers no pushback whatsoever against any of the changes, something which surely douses many a critic’s complaint that Hyams gutted Clarke’s original story. Clarke approves of every alteration without altercation. He even offers suggestions, ranging from still-scientifically-accurate-but-more-visually-engaging changes to key pieces of the story’s extrapolation of future space technology, to dropping an endless array of (in some cases fairly well-known) names within NASA, JPL, and various academic institutions who can advise Hyams on how certain events can be portrayed. He also has recommendations for vacation spots and places to eat, too – Clarke was a fountain of valuable information! (To be fair, all Clarke had to do was make suggestions and cash the checks, but it seems that he was fully on board with every change being made to strengthen the story as a film.)

Hyams comes across as a bit much-put-upon in his side of the correspondence (which is helpfully broken up into two distinct fonts so you can always tell who is saying what); he’s taking on a monumental task by himself, and he seems very aware that Kubrick looms large over his entire project. He knows comparisons will be made, and perhaps unflattering ones. “I feel the prop wash of 2001 buffeting my life. I am not making my film. I am the custodian of everyone else’s expectations. The only comfort is my total conviction in one belief: when a director puts the film together…. when you splice all of the artful performances… all of the endless dolly shots… all of the special effects… all of the careful backlighting… when you add all of them up… you have the story… nothing more and nothing less, making a film is like painting an enormous mural. … My salvation in this case is the fact that I am standing on the foundation of your remarkable concept. It is your story that will prevail… if it can survive my lack of talent.” Sometimes he sounds like he just wants to get it over with; a location scouting visit to the Arecibo Radio Telescope proves disheartening, as it turns out to be unsuitable for filming.

At other times, when sets are coming together and he’s signing top-tier talent like Roy Scheider, or having opening discussions with Douglas Rain and coming away feeling like he really did just talk to HAL, you can feel Hyams grooving on what a cool thing this movie could be. He admits to being a Kubrick fanboy, and he knows he’s lucky to be playing in the sandbox left tantalizingly open by the ending of 2001. Clarke is sympathetic throughout. Anyone skimming this book hoping to find some falling-out between the two…there’s no evidence of it here.

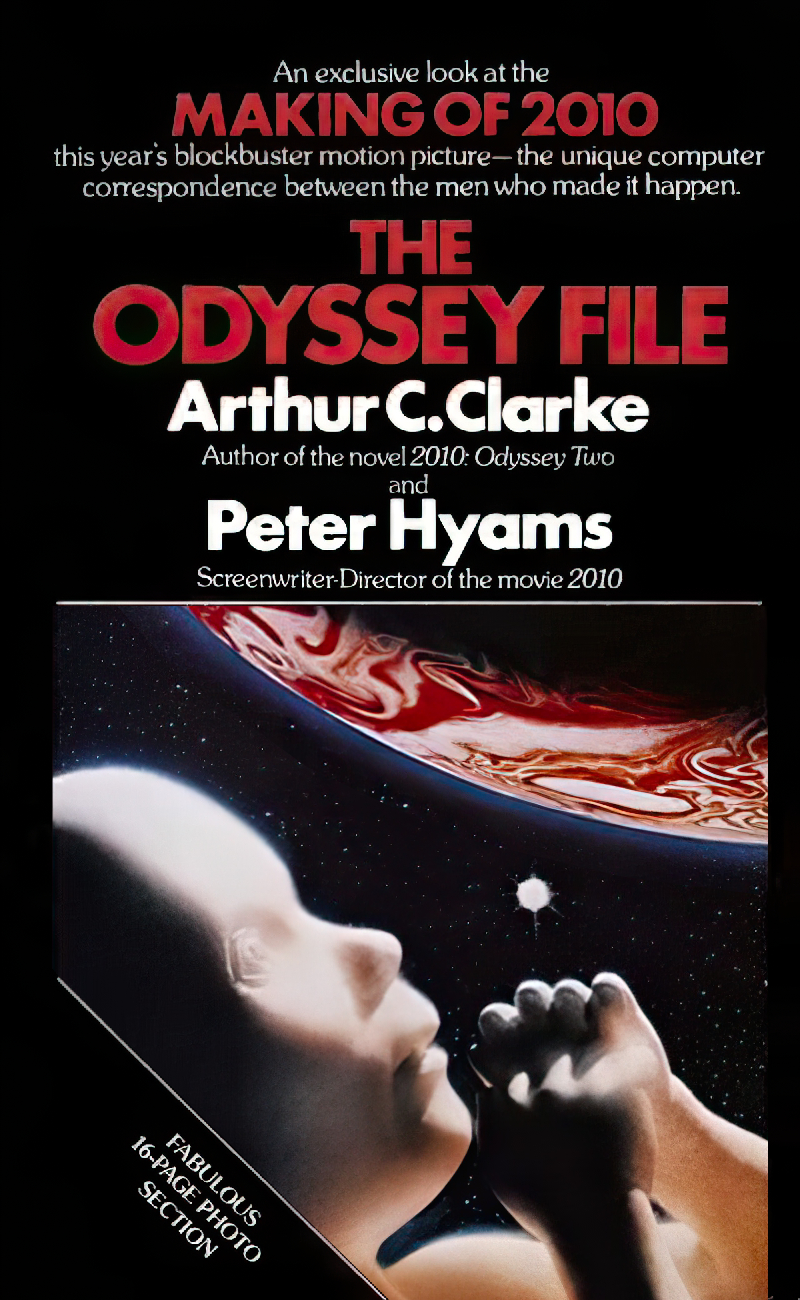

At the time, the book’s cover touted that it was a chronicle of a high-tech correspondence straight out of the future, and I suppose there’s some truth to that, as antiquated as it seems nearly 40 years later. The thought that a filmmaker and a leading genre author could directly connect their two Kaypro II computers via dial-up modems over satellite phone connections and exchange ideas and script notes was a “well, duh” to those of us who grew up in the age of the dial-up bulletin board system – of course this was how movies got made, why wouldn’t it be? And nearly four decades and a major pandemic later, we now see digital post-production and even music scoring being done in groundbreaking, remote/decentralized ways that are as new as this book’s electronic correspondence once was.

If there’s any disappointment, it’s that the book ends just as principal photography is about to begin. This is a record of how the movie was developed, but not the nuts and bolts of how it was filmed, promoted, and released. Surely there’s a whole other book that should’ve chronicled the physical production. But as a look at how a movie starts its life on the page, The Odyssey File is engrossing, if pleasantly unburdened by the kind of behind-the-scenes conflict that most people expect under these circumstances.

Year: December 3, 1984

Authors: Arthur C. Clarke, Peter Hyams

Publisher: Ballantine

Pages: 133