Back in the heady days of Nolan Bushnell-managed Atari, when the home versions of games like Pong and Stunt Cycle were making decent money, and the sky seemed to be the limit, and the 2600 was nothing more than a promising idea on the horizon, anything could’ve been the next big thing. And not even necessarily anything that was a video game. Despite all of the legendary stories of executive meetings in hot tubs, on-the-job marijuana use, and blue-jeans-as-businesswear, it may just be that nothing provides as much concrete evidence of the heady, psychedelic early days of Atari as one of their most obscure products: Atari Video Music.

Back in the heady days of Nolan Bushnell-managed Atari, when the home versions of games like Pong and Stunt Cycle were making decent money, and the sky seemed to be the limit, and the 2600 was nothing more than a promising idea on the horizon, anything could’ve been the next big thing. And not even necessarily anything that was a video game. Despite all of the legendary stories of executive meetings in hot tubs, on-the-job marijuana use, and blue-jeans-as-businesswear, it may just be that nothing provides as much concrete evidence of the heady, psychedelic early days of Atari as one of their most obscure products: Atari Video Music.

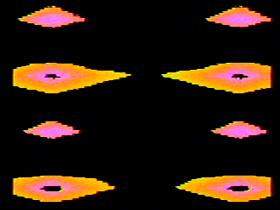

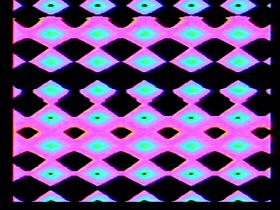

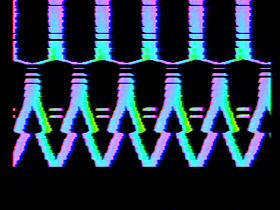

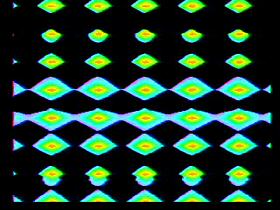

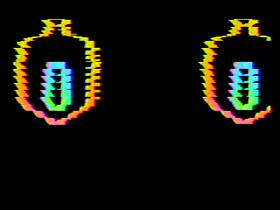

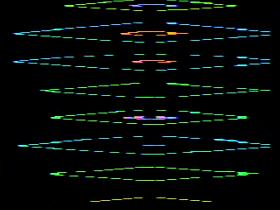

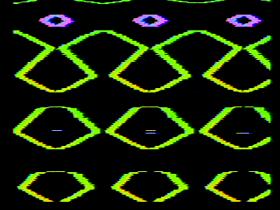

Simply put, Atari Video Music was a precursor to the “CD visualizations” that are now commonplace in home video game consoles and computer audio player programs. In 2000, it caused some consternation that Sony’s Playstation 2 lacked the colorful CD player visualization modes of the original Playstation – it was a standard feature and people expected it to be there. In 1976, however, it was hard to explain what Atari Video Music did, let alone why a product would be released that would create its effects (or, for that matter, why anybody would buy one). Video Music created blindingly colorful (and I don’t use that description lightly), psychedelic light displays that would pulsate and change depending on the intensity of the music.

Simply put, Atari Video Music was a precursor to the “CD visualizations” that are now commonplace in home video game consoles and computer audio player programs. In 2000, it caused some consternation that Sony’s Playstation 2 lacked the colorful CD player visualization modes of the original Playstation – it was a standard feature and people expected it to be there. In 1976, however, it was hard to explain what Atari Video Music did, let alone why a product would be released that would create its effects (or, for that matter, why anybody would buy one). Video Music created blindingly colorful (and I don’t use that description lightly), psychedelic light displays that would pulsate and change depending on the intensity of the music.

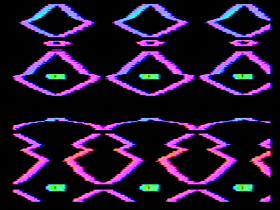

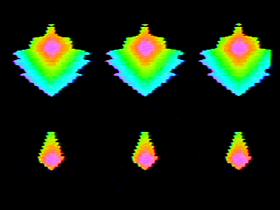

Of course, this being the 70s, Video Music was strictly analog, and to create even the limited effects that it produces, it was quite a bulky piece of woodgrain wizardry. (In the Phosphor Dot Fossils game museum, our Atari Video Music unit sits directly underneath the massive Atari 5200, and the 5200’s footprint is only slightly larger.) A series of buttons along the lower front panel of Video Music, ranging in warm colors from brown to tan, governs the unit’s basic functions (including the power switch, and whether or not the manual controls have any influence over the display). Above those, several knobs give the user manual control over intensity and various display parameters – allowing for solid or “donut” shaped displays, the degree of sensitivity to changes in the audio, and how many patterns would appear on the screen at a given time.

Of course, this being the 70s, Video Music was strictly analog, and to create even the limited effects that it produces, it was quite a bulky piece of woodgrain wizardry. (In the Phosphor Dot Fossils game museum, our Atari Video Music unit sits directly underneath the massive Atari 5200, and the 5200’s footprint is only slightly larger.) A series of buttons along the lower front panel of Video Music, ranging in warm colors from brown to tan, governs the unit’s basic functions (including the power switch, and whether or not the manual controls have any influence over the display). Above those, several knobs give the user manual control over intensity and various display parameters – allowing for solid or “donut” shaped displays, the degree of sensitivity to changes in the audio, and how many patterns would appear on the screen at a given time.

It’s hard to really explain just how bright Video Music’s displays are. As this piece of hardware comes from the era when game makers were only just learning that high-constrast displays could do permanent damage to TV screens if left on for a significant amount of time, its displays are incredibly high-constrast and incredibly colorful – maybe it’s a testament to a far trippier era, but it’s hard to watch it directly at length. (The most pleasing effect, in fact, comes from turning Video Music on, getting the music going…and then looking at the reflection of the colors on the opposite wall.)

It’s hard to really explain just how bright Video Music’s displays are. As this piece of hardware comes from the era when game makers were only just learning that high-constrast displays could do permanent damage to TV screens if left on for a significant amount of time, its displays are incredibly high-constrast and incredibly colorful – maybe it’s a testament to a far trippier era, but it’s hard to watch it directly at length. (The most pleasing effect, in fact, comes from turning Video Music on, getting the music going…and then looking at the reflection of the colors on the opposite wall.)

The designer of Video Music, Atari engineer Bob Brown, moved on to help design the company’s next big project, a programmable video game system, and his brainchild remained unique in the company’s history – really, for that matter, in the history of consumer electronics altogether. Video Music remains, to this day, a hard-to-find relic of Atari’s pre-Warner Bros. heyday in the 1970s.