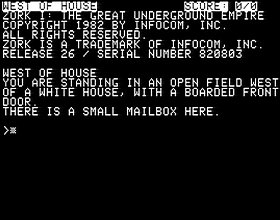

The Game: You are standing in an open field west of a white house, with a boarded front door. There is a mailbox here. (Infocom, 1982)

The Game: You are standing in an open field west of a white house, with a boarded front door. There is a mailbox here. (Infocom, 1982)

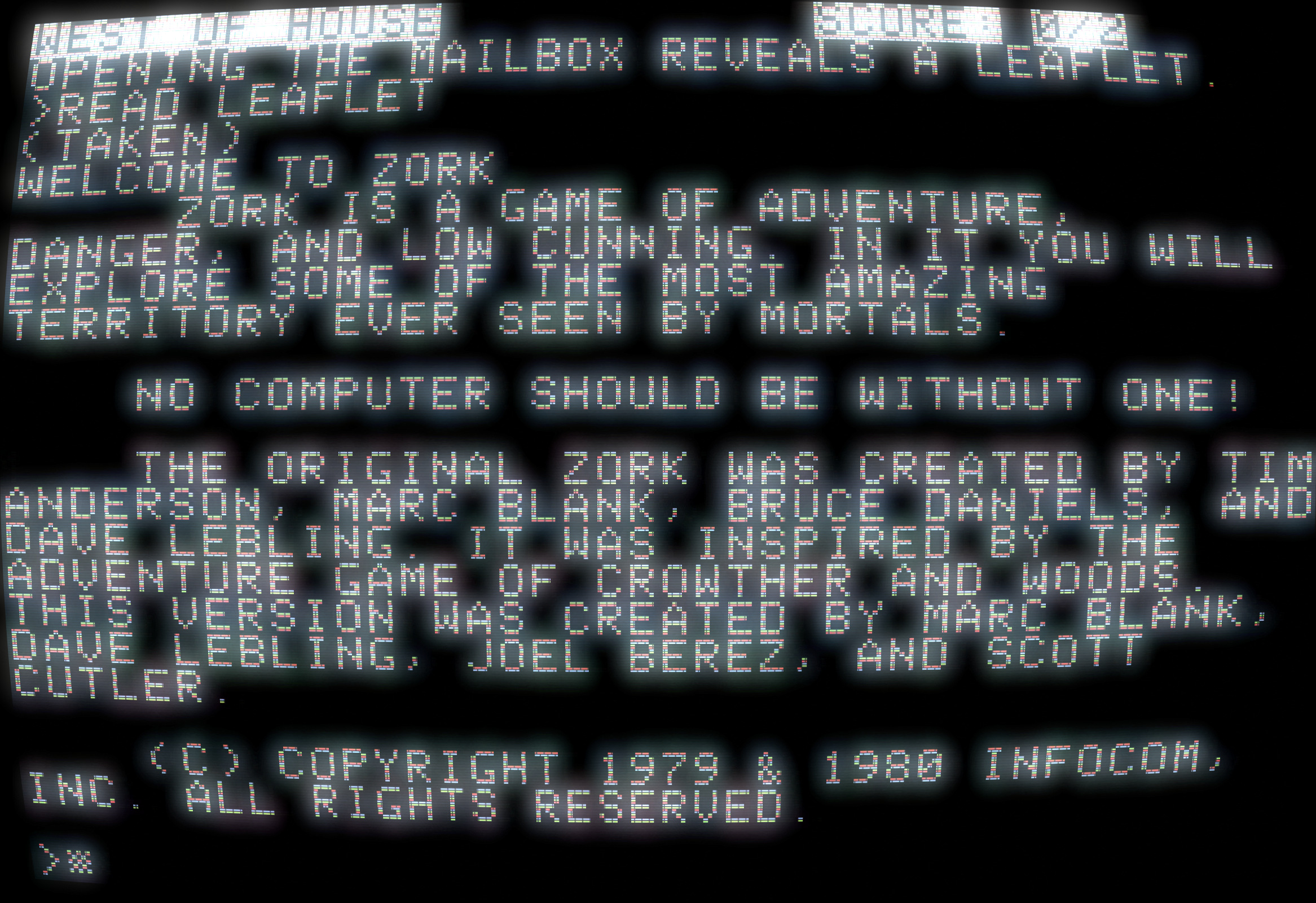

Memories: A direct descendant of the Dungeons & Dragons-inspired all-text mainframe adventure games of the 1970s, only with a parser that can pick what it needs out of a sentence typed in plain English. In truth, Zork‘s command structure still utilized the Tarzan-English structure of the 70s game (i.e. “get sword,” “fight monster”), but the parser was there to filter out all of the player’s extraneous parts of speech – anything that wasn’t a noun or a verb, the game had no use for. Many a player just went the “N” (north), “U” (up), “I” (inventory) route anyway.

Infocom also invented the strategy guide economy with the Zork series. Y’know how the latest modern titles pretty much require the strategy guide these days? It’s all Infocom’s fault – they started it with their Invisiclues hint booklets, each of which contained lots of “invisible” text which could be revealed by rubbing the inviso-pen included with each booklet over the clue in question. You could reveal one clue at a time, or unveil everything at once. And of course they cost you extra – and there was such a booklet for almost every Infocom text adventure out there, with the exception of their “junior level” titles, which packed the hint books in with the games themselves.

Infocom also invented the strategy guide economy with the Zork series. Y’know how the latest modern titles pretty much require the strategy guide these days? It’s all Infocom’s fault – they started it with their Invisiclues hint booklets, each of which contained lots of “invisible” text which could be revealed by rubbing the inviso-pen included with each booklet over the clue in question. You could reveal one clue at a time, or unveil everything at once. And of course they cost you extra – and there was such a booklet for almost every Infocom text adventure out there, with the exception of their “junior level” titles, which packed the hint books in with the games themselves.

Zork I was followed by two further games, as well as a second trilogy set in the Great Underground Empire; spinoffs like Zork Zero and the full motion video Return To Zork followed, along with a very short-lived series of novelizations. Though graphical adventures such as the Ultima series and the Wizardry games may have had more of a lasting influence, it was the concept of Zork as “interactive fiction” that ushered in the age of the CD-ROM as computer  gaming’s medium of choice. Remember Myst? Think Zork with lots of really nice pictures and you’re there.

gaming’s medium of choice. Remember Myst? Think Zork with lots of really nice pictures and you’re there.

For all the press it got at the time, even now Zork is a milestone of computer gaming.