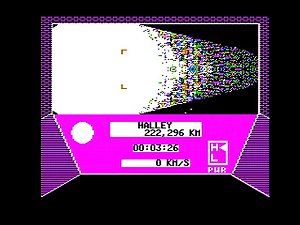

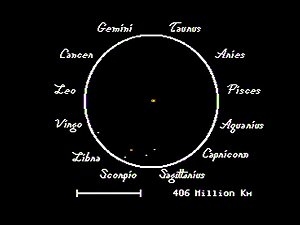

The Game: Your sleek spacecraft is launched from a base installation on Halley’s Comet (!). Your mission is to scout various bodies in the solar system – both planets and moons – which meet strictly defined criteria as dispensed by the computer. In some cases you must land, in others you must simply achieve orbit. You must learn to navigate the solar system using the constellations of the Zodiac, and learn to judge distance so you won’t overshoot your target (and therefore exceed your allotted mission time) with brief bursts of your faster-than- light drive. You climb in the ranks as you complete more missions. (Interscope, 1986)

The Game: Your sleek spacecraft is launched from a base installation on Halley’s Comet (!). Your mission is to scout various bodies in the solar system – both planets and moons – which meet strictly defined criteria as dispensed by the computer. In some cases you must land, in others you must simply achieve orbit. You must learn to navigate the solar system using the constellations of the Zodiac, and learn to judge distance so you won’t overshoot your target (and therefore exceed your allotted mission time) with brief bursts of your faster-than- light drive. You climb in the ranks as you complete more missions. (Interscope, 1986)

Memories: As a life-long space buff, I adored this game. I was always a big fan of such interplanetary missions as the Vikings, Voyagers, Pioneers and Mariners launched by NASA (and, for the most part, overseen by JPL, though to give credit where it’s due, the Pioneers were an Ames project). This game put me into the role of a surrogate space probe, navigating planets and their moons and generally exploring the solar system.

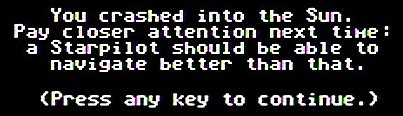

There are some minor control issues with the game’s faster-than-light drive (a somewhat unscientific necessity to prevent the game from dragging out to the actual eight years a trip to Jupiter or Saturn might take), but overall The Halley Project is a simple game to learn, and easy to become addicted to.

There are some minor control issues with the game’s faster-than-light drive (a somewhat unscientific necessity to prevent the game from dragging out to the actual eight years a trip to Jupiter or Saturn might take), but overall The Halley Project is a simple game to learn, and easy to become addicted to.

As I mentioned above, the creators of The Halley Project took some big liberties with scientific fact, which could create some confusion as to whether or not this was truly an educational  game as it was billed. The base on Halley’s Comet, landings on the surfaces (!?) of giant gas worlds, and the FTL engine were just some of the divergences from known physics featured in the game. But hey, I knew these things were unlikely or impossible when I opened the box, and I still played the game.

game as it was billed. The base on Halley’s Comet, landings on the surfaces (!?) of giant gas worlds, and the FTL engine were just some of the divergences from known physics featured in the game. But hey, I knew these things were unlikely or impossible when I opened the box, and I still played the game.