The Game: You control a “Chemic,” a free-floating object while can adhese itself to passing Moleks, but is vulnerable to the Atomic. Within a limited amount of time (charted by a meter at the bottom of the screen), gather and repulse Moleks around your Chemic until you’ve duplicated the example shape shown in the center of

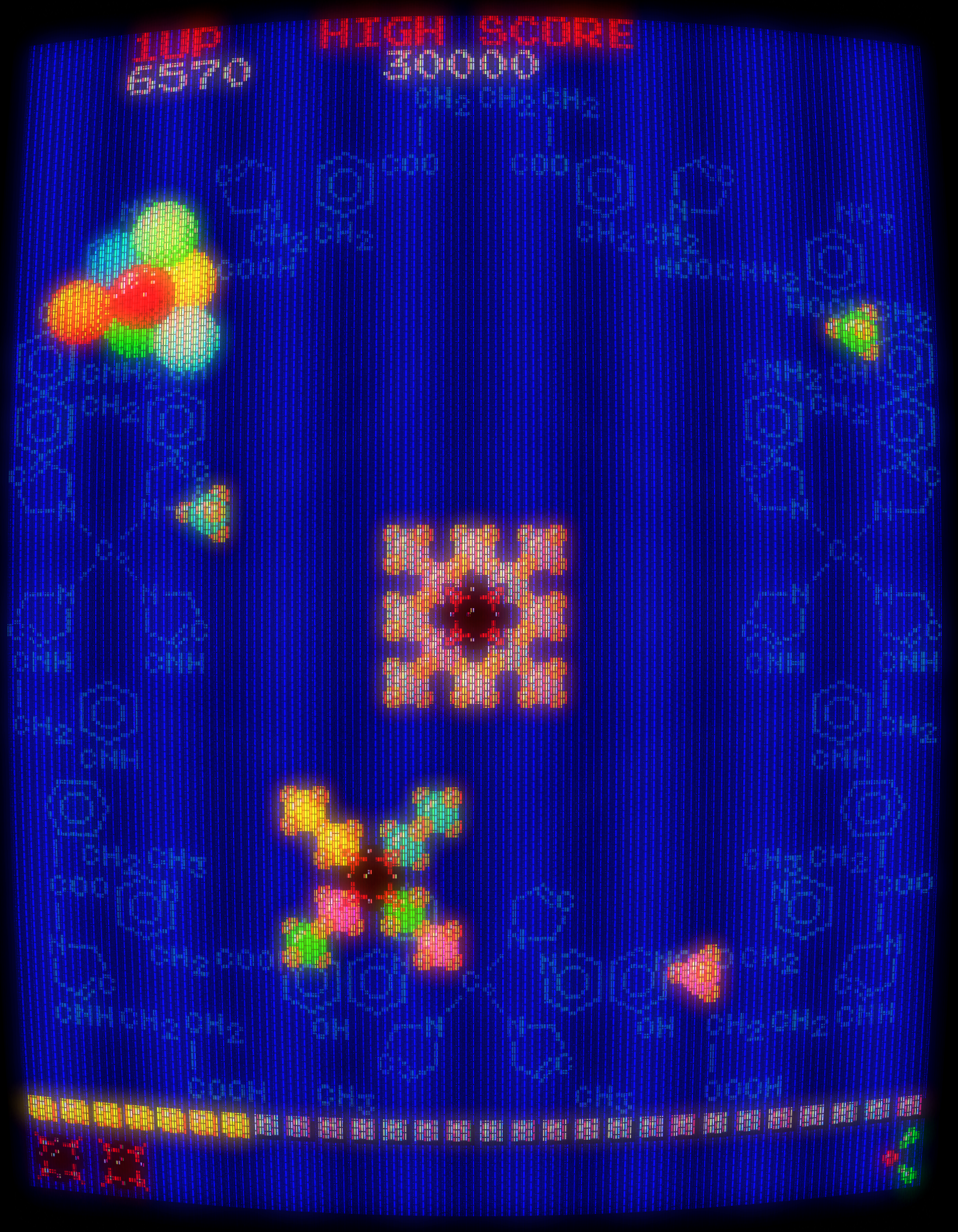

The Game: You control a “Chemic,” a free-floating object while can adhese itself to passing Moleks, but is vulnerable to the Atomic. Within a limited amount of time (charted by a meter at the bottom of the screen), gather and repulse Moleks around your Chemic until you’ve duplicated the example shape shown in the center of  the screen. Beware of the Atomic, however – it will not only become more aggressive in its deceptively aimless wanderings, but it can also separate into its own component molecules – and regather its shape right in your path. It also shoots, in later levels, energy that can dislodge Moleks from the Chemic’s pattern. You advance through the game by successfully duplicating the sample shape – and surviving the Atomic’s attacks. (Namco, 1983)

the screen. Beware of the Atomic, however – it will not only become more aggressive in its deceptively aimless wanderings, but it can also separate into its own component molecules – and regather its shape right in your path. It also shoots, in later levels, energy that can dislodge Moleks from the Chemic’s pattern. You advance through the game by successfully duplicating the sample shape – and surviving the Atomic’s attacks. (Namco, 1983)

Memories: If someone pinned me up against the wall and demanded that I name my favorite coin-op manufacturer – and I’ll admit that this isn’t terribly likely to happen – I’d have to say Namco. They brought us such immortal and inexplicably (and insanely) fun games as Pac-Man, Mappy, Dig Dug, Galaga, Motos, Pole Position and Warp Warp – to name just a few. Among these popular titles are games so indescribably weird that they almost defy description, but I have to hand Namco the prize for sheer conceptual brilliance. Phozon, more obscure than any of the games mentioned above (even moreso than Motos, which is pretty esoteric itself), may well be the first video game ever to concern itself with molecular bonding. Phozon represents one of the biggest cognitive challenges in the early heyday of the arcades: avoid the enemy, but also gather the pieces necessary to turn one’s own onscreen avatar into a pretty but unwieldly shape. Sooner or later, you wind up being too big a target for the Atomic to miss.

Phozon‘s an audiovisual treat as well, with some eye-poppingly colorful graphics (the rotating-pyramid-of-spheres adversary that chases you around the screen isn’t a bad piece of graphics/animation work for 1983) and mind-boggling background graphics (the chemical-diagram background of World 1 is beyond merely cool, given the game’s subject matter) and some inspired calliope-like music. It’s easy to play too – but a bear to beat. And it’s addictive too, did I mention that? Fair warning.

The thought occurs that on some levels, Phozon could be compared to Reactor, a game which casts you as a subatomic particle trying to keep a nuclear reactor from blowing, but the similarities end there. They’re both conceptually unique games which turn microscopic objects into big-time fun. Phozon is almost

The thought occurs that on some levels, Phozon could be compared to Reactor, a game which casts you as a subatomic particle trying to keep a nuclear reactor from blowing, but the similarities end there. They’re both conceptually unique games which turn microscopic objects into big-time fun. Phozon is almost  completely unknown in the U.S., but was popular enough in Japan to merit inclusion on Namco Museum 3 on both sides of the Pacific. I highly recommend those of you with access to a Playstation to pick it up and try it out. And clear your schedule for the rest of the day when you do.

completely unknown in the U.S., but was popular enough in Japan to merit inclusion on Namco Museum 3 on both sides of the Pacific. I highly recommend those of you with access to a Playstation to pick it up and try it out. And clear your schedule for the rest of the day when you do.